The findings come from a new report by

Afrobarometer, a pan-African, non-partisan research network, which conducted face to face interviews with about 50,000 citizens across 35 African countries.

The trend is very recent: in roughly four years between consecutive surveys, from 2011 to 2015, "lived poverty" fell in 22 of 33 countries surveyed in both rounds.

But while the continent can no longer be considered poor overall, poverty is still a widespread issue, and huge differences remain from country to country.

Mauritius, the least poverty-stricken country, scores 0.10 on the Lived Poverty Index -- which measures how frequently people go without basic necessities such as medical care, clean water and food during the course of a year.

On the other hand Gabon, the poorest among the surveyed countries, has a rating of 1.87. The continent's average is 1.15.

This means that in Mauritius 4% of people went without food in the past year, compared to 74% in Gabon.

The survey highlights differences in access to basic services: while in Liberia 78% of people went without medical care at least once in the past year, in Cape Verde it was just 19%.

"More people are living better lives -- that's good news for Africa," says Robert Mattes, lead author of the report, and University of Cape Town professor.

"Of course, we'll need to verify that these trends hold up in our next round of surveys, before we celebrate."

Poverty is still widespread

Despite low poverty levels in countries such as Mauritius, Cape Verde, Algeria, Egypt and Tunisia, lived poverty is still widespread on the continent.

The report shows that lived poverty actually increased in five countries - most steeply in Mozambique, Benin, and Liberia - and remained stagnant in five others.

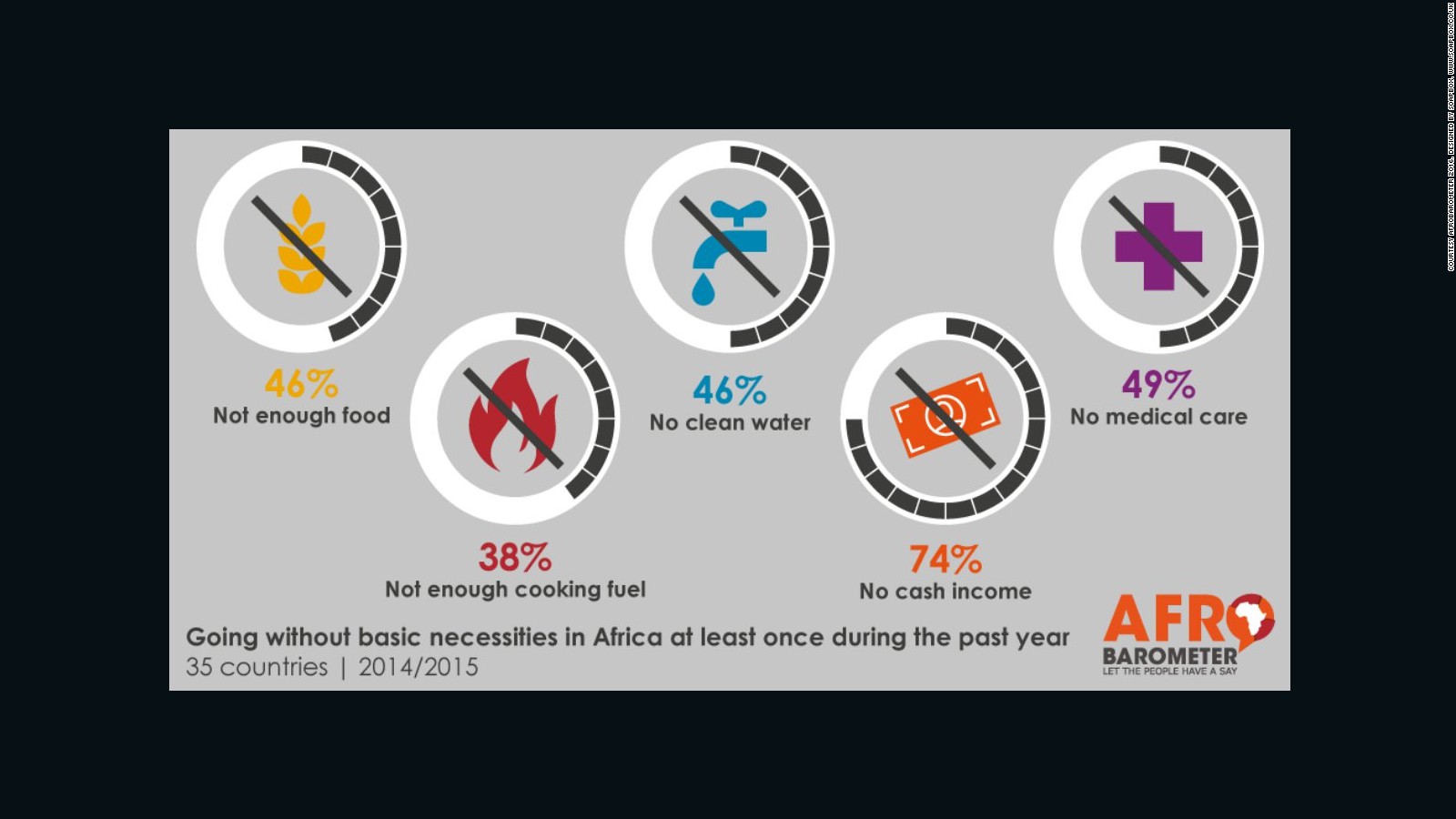

On average, in 2014/15 over 40% of people said they went without clean water or food at least once or twice in the past year. 49% went without medical care, 38% without cooking fuel and 74% without cash income.

Governments need to act

Although the general growth in African economies definitely plays a role in the reduction of poverty, Afrobarometer warns there is no systematic relation: the crucial factor in improving people's lives is "the extent to which national governments and their donor partners put in place the type of development infrastructure that enables people to build better lives," the report says.

"Where governments do relatively simple things like invest in secondary and tertiary education, build good roads, and other development infrastructure like sewage systems and electricity grids, people are substantially better off," says Mattes.

Across the continent people's experiences differed greatly. Those living in Central and West Africa said they often went without basic necessities such as clean water and medical care, whereas North Africa experienced much fewer shortages.

On a person to person level, Africans who were employed full-time, had a high level of education, and lived in an urban area where basic infrastructure was in place, said they were rarely short of basic necessities.

"In other words, if governments and donors build an enabling environment, people seem to find ways to provide for themselves."