Business

Death of a Shale Man: The Final Days of Aubrey McClendon

Meet Mr. Gas: Aubrey McClendon (Fortune, 2008)

Editor’s note: On March 2nd, natural-gas industry pioneer Aubrey McClendon, 56, was killed in a fiery, single-car crash in Oklahoma City, Okla., one day after being indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of conspiring to rig the price of oil and gas leases. McClendon rose to prominence as the outspoken cofounder and CEO of Chesapeake Energy. He was forced out of Chesapeake in 2013 and formed a new company called American Energy Partners. This 2008 profile of McClendon from Fortune‘s archives appeared just as the fracking boom was gaining momentum--along with the executive’s reputation as a provocateur.

That guy just called the governor of Connecticut a liar.

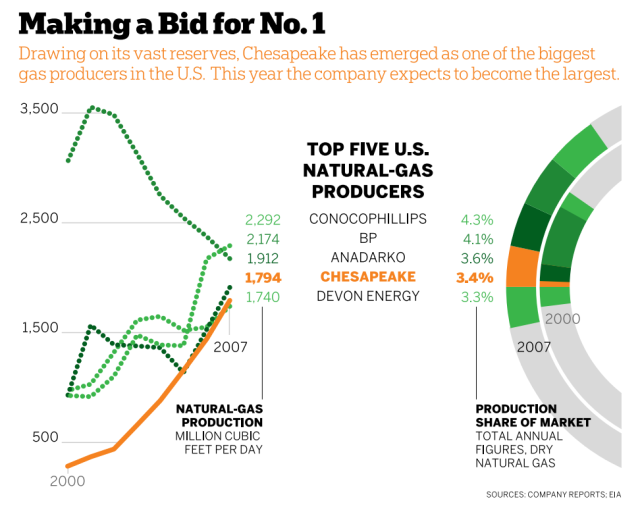

That guy at the podium. Everybody listening in the Blue Room today knows who he is--they work here, he’s the boss--but do you? He’s Aubrey McClendon. He’s worth more than $3 billion. He’s co-founder and CEO of Chesapeake Energy . It’s a natural-gascompany, okay? Headquarters in Oklahoma City, $25 billion market cap, No. 324 on this year’s Fortune 500. Already the most active driller for gas in the U.S., by a factor of two, and soon to become the country’s biggest gas producer. Is any of this ringing a bell?

You can bet it is with Jodi Rell. Last fall the Connecticut governor sent an angry letter to the chairmen and ranking members of two congressional committees that included the phrase “unconscionable fleecing of U.S. citizens by natural-gas suppliers who ‘elect’ to reduce production in order to drive up prices paid by their captive customers.” She asked for an immediate investigation into possible price manipulation. The only company mentioned by name was Chesapeake Energy.

Turns out the governor was grandstanding. No investigation ever materialized. McClendon could have just let it drop. Probably should have. “Maybe that’s the way Exxon wants to run their business,” he says now, warming to the tale, feeding off the crowd as he relates the story in this corporate town hall meeting, “but you tell me--and when you tell me, you’re also saying to all our employees--that we did something wrong when we didn’t do anything wrong, I’m gonna come out swinging and fighting, and that’s what I did.”

McClendon fired off a five-page rebuttal, fairly dripping with sarcasm, that found its way into in-boxes all over the country. (David Crane, the outspoken CEO of NRG Energy in Princeton, N.J., remembers it well. “He doesn’t back down from a fight,” Crane says admiringly. “That went beyond anything even I would do.”) He concluded with an invitation, which read like a challenge, to Governor Rell to meet with him during his upcoming visit to “the Nutmeg State.” The governor declined. (She also declined to comment to Fortune.) “Her spokesman said they didn’t want to get into a war of words,” says McClendon, setting up his punch line. “That’s fine. I just told them I didn’t think liars ever wanted to get in a war of words.”

McClendon doesn’t seem like that guy when you get him one-on-one. At 48, he’s built like a runner, eats muesli with berries for breakfast, favors striped shirts with his blue pinstripe suits, wears his wavy hair casually long. He didn’t go to Oklahoma or Oklahoma State; he went to Duke. He studied history, not geology or business. He has a finely tuned aesthetic sense reflected in the stately red-brick Chesapeake corporate campus on the north side of Oklahoma City. (He personally oversaw the design.) A creek flows through it. “I’d rather look at flowers than red dirt,” he says.

That said, McClendon’s middle name is Kerr. He comes from a long line of Oklahoma oil and gas men, starting with his great-uncle Robert S. Kerr, who was born in a log house with no windows, made his fortune when he co-founded Kerr-McGee, and went on to serve Oklahoma as its first native-born governor and later in the Senate. Robert S. Kerr, of whom it was once said by the late House Speaker Sam Rayburn, he’s the kind of man who “would charge hell with a bucket of water and believe he could put it out.”

Now that sounds more like the guy at the podium, and not just when he’s going after Governor Rell. His flair for confrontation finds many outlets. A year ago McClendon jumped on Governor Joe Manchin of West Virginia, threatening to halt plans to build a new regional headquarters in Charleston after a county jury awarded plaintiffs $404 million in a case involving a Chesapeake subsidiary. When former Oklahoma Representative Brad Carson--a conservative Democrat, but a Democrat nonetheless--ran for the Senate in 2004, McClendon donated more than $1 million to a pair of right-wing 527s (tax-exempt, loosely regulated political groups) that spent part of the money on attack ads in Oklahoma. When McClendon discovered a pristine parcel of dunes and wetlands while jet-skiing on Lake Michigan, he snatched it away from local groups that had been trying to preserve it for decades (“completely dysfunctional” is how he dismisses those groups) and announced plans to develop it. And when he and a posse of sports-loving buddies decided it would be cool to bring the NBA to Oklahoma City, they bought the Seattle SuperSonics from Starbucks founder Howard Schultz and set about prying the team loose from the community where it’s been rooted for 41 years. Schultz is suing to stop the move, but he may be too late. On April 18 the NBA owners voted 28-2 to approve it.

This is McClendon’s moment, and he’s not backing down. U.S. natural-gas prices are soaring, nearly doubling since last summer. Markets are expanding, thanks to surging economies in Asia and growing demand for relatively clean-burning gas from electricity producers at home. Evolving government policy with respect to global warming is turning the tables on his biggest competitor, coal.

Just nine years ago Chesapeake was worth all of $30 million, had $1 billion in debt, and couldn’t find a buyer at 75 cents a share. Today it’s a $50 stock--up more than 50% over the past year in a down market. And McClendon insists that its real value is closer to $100. Why? Simple. Not only does Chesapeake have 11 trillion cubic feet of proven reserves, but it’s sitting on the country’s largest stockpile of unproven reserves (100 trillion cubic feet) and the largest inventory of undrilled wells (some 35,000).

Then there’s Chesapeake’s latest find, just announced: the Haynesville Shale, a vast new play in northwestern Louisiana that all by itself could yield the company as much as 20 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. It might be one of the biggest domestic gas fields ever discovered. No wonder McClendon is buying Chesapeake stock every chance he gets. He’s invested $100 million of his own money in the past 12 months, upping his stake to 31 million shares.

Haynesville is a huge bet, for both McClendon and his company. Risky? Sure. Chesapeake just sold 20 million new shares to begin to cover the exploration expenses. And Gimme Credit high-yield analyst Carl Blake sees more heavy borrowing in Chesapeake’s future. “Unfortunately, it’s going to take a lot more capital to monetize those assets,” says Blake. If gas keeps trading above $10 per million British thermal units (BTUs) or, as many analysts expect, goes even higher, then McClendon should be covered. If not, well, we’ll see. In any case, he’s not backing off. That’s not how he got here.

“Have you ever heard of Amy Street?” McClendon wants to know. This interview began the wrong way, with McClendon asking all the questions. He knows how old I am, how many kids I have, where I went to college, what my major was. Amy Street, he says, is in Providence. It’s the inspiration for AmieStreet.com, a little company he’s backing with some of his VC money that “aspires to remake the indy music business.” (It was news to me. Then a couple of weeks later the site got a dash of unexpected publicity when the Eliot Spitzer sex scandal broke: AmieStreet.com is where escort Ashley Alexandra Dupr? peddles her MP3s “What We Want” and “Move Ya Body.”)

But investments in edgy dot-coms don’t begin to explain what all McClendon does with his wealth. He owns half a vineyard in Bordeaux, a soda-pop stand and a tree farm on Route 66, stakes in ten restaurants, and 110,000 acres of ranch, timber, and farm land, which makes him one of Oklahoma’s biggest landowners. In the past few years he’s built a $3 million Olympics-worthy boathouse on the Oklahoma River, given $20 million to Duke, and contributed some $15 million to the University of Oklahoma. He gave $1 million to the Red Cross after Hurricane Katrina and handed out a fistful of $100 bills to the roughnecks he’s pictured with in the photograph that opens this story.

And it all comes from natural gas. In the beginning, back in the early 1980s, it was just McClendon and Tom Ward, a couple of self-employed land men in their early 20s (born three days apart) scouring courthouse records and real estate transactions, snapping up leaseholds wherever they could find them, sprinting to stay one step ahead of the majors. McClendon certainly had a cushion. (His wife, Katie, is a Whirlpool heiress.) But Ward says his partner always worked even harder than he did. They had a deal, sealed with a handshake (no lawyers, no paper), to cut each other in fifty-fifty on whatever either of them found. McClendon took the southern and eastern parts of the state; Ward, who came from tiny Seiling, Okla., took the western.

That arrangement lasted six happy years, until it dawned on them that they probably had enough experience by then to dig some of that good rock themselves rather than turn it all over to somebody else. They got a lawyer this time, one of McClendon’s high school buddies. Kicked in $50,000. Incorporated as Chesapeake Energy in 1989, with Aubrey as CEO, Tom as COO. (Ward left, amicably, in 2006 and is now CEO of SandRidge Energy.) The name choice was McClendon’s. He had an idea that big companies--ambitious companies--should never carry the founders’ names, the better to attract big, ambitious talents down the road. But why Chesapeake? Nice sound to it, that’s all.

Quickly they were in over their heads. Drilling demands huge upfront investments--in land, equipment, and personnel. They went public to feed the beast. “We had to have investors,” says Ward. “We had to have capital.” If it wasn’t the worst IPO of 1993--well, that’s how they remember it. It went off at $1.33 a share and dipped below $1 (not for the last time), but then it recovered. For three tipsy years during the mid-1990s, Chesapeake was the top-performing stock in America--any sector, any exchange. McClendon says he never believed it. He felt captive to momentum investors, but what can a CEO do in a situation like that? Only one honorable choice: Don’t sell your shares to some sucker. So when some wells turned up dry in late ’96, prices plunged, and Chesapeake’s stock collapsed, McClendon and Ward went down with it. They were back where they started.

For a while it seemed that selling the company was the only way out. Chesapeake and rival Devon Energy, another Oklahoma City company, were at the top of every investment banker’s pitch list in those days. Chesapeake did get one nibble, from an Oklahoma utility looking to scoop up gas reserves on the cheap. The offer was for $2.25 a share, a 25-cent premium. Aubrey held out for $3. The offer went away. Nobody was going to save McClendon and Ward, it was becoming clear, except maybe themselves.

We come now to the money moment in the saga of Chesapeake Energy. Right around the turn of the century. Anybody who’s paying any attention to Chesapeake is saying these guys are toast. Gasprices are the pits. The stock is nearly worthless. The debt is frankly overwhelming--$1 billion. The thing about it, though, is that the notes aren’t due for seven years. So McClendon and Ward have time, and they have a plan: Natural gasis tremendously underpriced, they tell their board, and we’re going to do everything we possibly can to position ourselves for the inevitable recovery.

How do they know that? It’s 2000 now. McClendon is in San Jose visiting Calpine, one of the new breed of merchant electric-power companies to emerge from deregulation. Unlike Chesapeake, Calpine is soaring. It has big plans to build new plants. McClendon is taking it all in. “And I said, ‘Let me get it right,'” McClendon recalls. “‘If you guys build this many megawatts and your competitors build this many megawatts, and 90% of it comes from natural gas, remind me how natural-gas prices are going to stay low forever.’ And their response was, ‘They’ll stay low because they’ve always been low. And No. 2, it doesn’t matter because our plants are more efficient than our competitors’, so even as prices rise we’ll still make money.’ I went away from that meeting saying, ‘We got a chance.'”

Really all he had so far, though, was a customer. Potentially a very good customer, absolutely. Utilities are less price-sensitive than industrial consumers are, and the electricity market was growing. McClendon could see that. Not like a hockey stick. More like 2% a year, up from 1%. But it was meaningful, the steady growth driven by a timely cluster of long-term trends: The explosion of the Internet. The mad proliferation of music players and flat-screen TVs--all that stuff that gets plugged in. And the great unstoppable migration from the Northeast to the South and the Southwest, which matters because, as a rule of thumb, it takes three times as much energy to cool a room as to heat it. So now McClendon needed more reserves.

Everybody always knew there was a lot of gas locked up in shale. The question was how to get at it. McClendon and Ward’s genius--the insight that would not just rescue Chesapeake but would make them billionaires--was recognizing that higher prices would enable new technology, thereby opening up vast new plays that had been ignored. Gasat $2 per million BTUs, which is where it was eight years ago, is strictly a conventional-well proposition; nothing else makes economic sense. Gas at $6, $8, and even $10 per million BTUs, which is where Aubrey and Tom correctly saw the market moving, enables so-called horizontal drilling. You can bore two miles straight down into a bed of shale, hang a 90-degree turn, blast the rock at regular intervals with 10,000 pounds per square inch (psi) of hydraulic pressure to create fractures through which gas can flow, and still make money. “Nobody could imagine that from rock that has almost no permeability you could get gas to flow in commercial amounts,” says McClendon. “We weren’t the first to unlock those secrets, but we were among the first to recognize that if it works it changes everything.”

They bet big, “went long natural gas,” is how Ward puts it. Piled debt on debt, and okay, maybe they overspent on land. Thing is, says McClendon, there were “tens of millions of acres of opportunity that once you seized them, there wouldn’t be another opportunity.” They snapped up land in Texas, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Louisiana. Established a huge presence around the gas-rich Barnett Shale near Fort Worth, drilling at Colonial Country Club, in the parking lot at the Texas Christian University football stadium, underneath runways and terminals at the Dallas-Fort Worth airport.

McClendon and Ward made it a pure play, kept the focus on gas. Nothing overseas. (“We don’t take foreign political risk,” says McClendon.) Nothing offshore. (“We don’t take hurricane risk.”) Everything well east of the Rocky Mountains. (“We’re not trying to pick fights with environmentalists.”) And while the big bet on rising prices drove strategy, they also became experts at hedging out weather-related volatility. “In the past this industry’s always been a price taker, Rockefeller aside,” says McClendon. “We believe that we are price makers. We need some cooperation from the market, but we don’t need much.”

McClendon has been writing checks to politicians for nearly two decades, leaning right, heavily, but aiming to cover every base. (Clinton got a check last June; Obama got his in February.) His breakout year was 2004, when in a span of 56 days leading up to the November elections he made contributions totaling $2,125,000 to a clutch of right-wing 527s: Progress for America Voter Fund, Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, Republican State Leadership Committee, Club for Growth, and Americans United to Preserve Marriage.

Club for Growth and Americans United to Preserve Marriage went hard after Oklahoma Democrat Brad Carson. Picking a fight on same-sex marriage was Ward’s idea, McClendon says now, done at the urging of Ward’s friend and fellow Christian conservative Gary Bauer. McClendon kicked in $625,000; Ward, $525,000. A part of their treasure paid for a nasty TV spot in Oklahoma that suggested Carson was secretly in favor of same-sex marriage (even though he had voted against it in the House) and seemed also to imply that he was gay. “We never dreamed that it would become controversial,” McClendon says now, adding that he has a brother-in-law who is gay and that he’s campaign co-chair for corporation commissioner Jim Roth, the first openly gay elected official in Oklahoma. “We just thought we were doing what everybody else did when they gave money to … 427s? 527s? Whatever it is.” Whatever. The bottom line for McClendon is that Brad Carson got trounced.

Maybe none of this would have come back to bite McClendon so hard if two years later, in 2006, he and Ward had not pitched in with McClendon’s best friend, Clay Bennett, and five other Oklahomans to buy the Sonics. Hearing about their political shenanigans gave the good people of Seattle all the more reason not to trust them. Speaking in public, Bennett, the principal owner, was clear: He and his Oklahoma buddies would keep the Sonics in Seattle.

Of course nobody believed him. Still, it came as at least a mild shock last summer when McClendon told the Oklahoma Journal Record, “But we didn’t buy the team to keep it in Seattle; we hoped to come here.” Afterward McClendon backpedaled (“It was my fault for saying something that was not accurate,” he told me), but he still had to pay a $250,000 fine to the NBA. Then they all looked like idiots when this e-mail exchange from April 2007 surfaced recently in a suit brought by the City of Seattle to try to prevent the Sonics from breaking their lease:

Tom Ward: Is there any way to move here [Oklahoma City] for next season or are we doomed to have another lame-duck season in Seattle?

Clay Bennett: I am a man possessed! Will do everything we can. Thanks for hanging with me boys, the game is getting started!

Tom Ward: That’s the spirit!! I am willing to help any way I can to watch ball here [in Oklahoma City] next year.

Aubrey McClendon: Me too, thanks Clay!

McClendon’s latest obsession cuts a little closer to the heart of Chesapeake’s interests: He’s on a campaign to expand the market for natural gas. In February 2007 an organization calling itself the Texas Clean Skies Coalition placed ads in newspapers across the state to oppose utility giant TXU’s plan to build new coal-fired power plants. The ads featured pictures of sad-looking people with coal-like soot on their faces, as well as facts and analysis lifted from a website operated by the Environmental Defense Fund. “We don’t know who they are or where they’re from,” the Environmental Defense Fund said in a hastily issued press release the day the ads appeared. Turns out it was Chesapeake.

Since then McClendon has created the American Clean Skies Foundation in Washington, D.C. It puts out a glossy journal printed on biodegradable polypropylene. (“No trees were harmed in the production of this magazine.”) CleanSkies.tv, a web-based news channel (“Content will be fair and fact-based”), launched on Earth Day.

This new role for McClendon--as champion of the environment--is not obvious casting. He’s a huge supporter, after all, of Oklahoma Senator Jim Inhofe, who claims global warming is a “hoax.” But here he stands nonetheless, at what he acknowledges is “a nice intersection between my moral thoughts about the problem and my economic thoughts about the problem,” pushing a very big story. A story about a new era for the American economy, when natural gas is plentiful and cheap, American manufactured goods are more competitive in the global marketplace, our balance-of-payments deficit declines because we import less oil, our skies are cleaner because we burn less coal, global warming slows down, and ordinary Americans in out-of-the-way places get rich on royalty checks from gas companies. It assumes that gas prices will rise, but not as fast as oil prices. And that not just electricity producers (who today use more coal than gas) and homeowners (who use a lot of heating oil) but also cars and trucks will come to rely increasingly on natural gas. And it’s nothing if not audaciously ambitious. Just like McClendon himself.

“I think our community, our state, our country, and our world need us to be successful,” McClendon says, wrapping up his remarks to the Chesapeake employees gathered in the Blue Room. It’s cozy in here, and the d?cor lives up to the name. Blue carpet, blue vinyl upholstery, and glowing blue walls that suggest a gas oven on full broil. Packed from pit to rafters, everybody paying close attention to their leader. “We’re doing things that nobody else in the world is doing,” he continues. “Drilling wells that other people wouldn’t have. We’ve made discoveries that other people would never have found. When I wake up in the morning I’m ready to go because I get to work for a company that drilled more rock than anybody else on earth …” Wait, did that guy just say Chesapeake is the No. 1 driller on the planet? It’s just the U.S., actually, for now. The world will have to wait.

This article was originally published in the March 12, 2008 issue of Fortune.

Death of a Shale Man: The Final Days of Aubrey McClendon

Aubrey McClendon: His Final Days

- Busy agenda of wheeling and dealing in days before fatal crash

- From gas deals to Oklahoma River white-water kayaking project

Aubrey McClendon awoke that Tuesday, as he had 10,000 times before, ready to work a deal.

McClendon, co-founder of Chesapeake Energy Corp., had ridden more wild ups and downs in America’s energy patch than just about anyone. But on March 1, as the world closed in on him, McClendon had something else on his mind. That morning he was e-mailing about a riverfront development in his hometown of Oklahoma City, the place where he’d gambled so much for so long.

The 56-year-old sounded upbeat, optimistic -- he sounded, in short, like himself.

Twenty-four hours later, he was dead.

Firemen examine McClendon’s Chevy

Source:KWTV News9

By now the world knows the broad outlines. On the morning of March 2, hours after being accused of rigging bids for oil- and gas-drilling rights, McClendon slipped away from his security team and climbed into his 2013 Chevy Tahoe. He sped north along a lonesome two-lane stretch of Midwest Boulevard, toward the prairie-scrub city edge, where he drove his SUV into a wall at high speed.

The news reverberated through Oklahoma City like a thunderclap. There, and as far away as Riyadh and Caracas, everyone in the energy game knew the backstory. McClendon, the man who’d told OPEC to go to hell, had vowed to fight the indictment. Then this: the tragic end to a life that seemed to epitomize America’s shale boom -- and its bust.

A week on, with many still struggling to make sense of it all, the circumstances surrounding McClendon’s death are only now coming into focus. Police in Oklahoma City say they have yet to determine if the crash, which involved no other vehicle, was intentional. Emails McClendon sent to business associates hours before held no clues, no hints of trouble.

"It is hard for us to comprehend that he is really gone,” Tom Blalock, an executive at American Energy Partners LP, the venture McClendon founded after Chesapeake ousted him, told the some four-thousand people gathered at Crossings Community Church in Oklahoma City on Monday at a public memorial.

Yet, right to the end, McClendon seemed to be hatching plans.

McClendon in 2012

Photographer: Sue Ogrocki/AP

That was pure McClendon. His rise and fall was the stuff of legend. He grew to become a towering figure by building Chesapeake into a $37.5 billion company, thanks to his championing of controversial hydraulic fracturing. But the very gas boom he helped create caused prices to plummet, clipping the company’s value by more than half and triggering a shareholder revolt that led to McClendon’s ouster.

He then formed American Energy Partners and raised more than $10 billion to amass drilling rights from the Appalachian Mountains to Australia and Argentina. But that business, too, would soon buckle under the weight of collapsing energy prices.

This is the story of his final days, pieced together from interviews with people who spent time with McClendon or were in touch with him during his last week of life. The picture that emerges is one of a man emboldened and energized -- and eager to turn a new corner.

Cutting Ties

Like everyone in the shale patch, McClendon -- cocky, bold, seemingly indefatigable -- had been staring down the collapse in energy prices for months. But his world darkened considerably in the week before the crash. As of Friday, Feb. 26, one of his biggest financial backers, the Energy & Minerals Group, a private-equity firm led by John Raymond, had all but cut ties with him, according to a letter Raymond later sent to investors. That raised immediate questions about American Energy’s viability.

That afternoon, he drove over to Pops on Avondale Drive in Nichols Hills Plaza, one minute away from his sprawling white stone house. A modern rendition of a classic mid-century diner, Pops features about 500 types of soda, from Catoosa Cream to Grape Plains, and an All-American menu ranging from BBQ wraps to quarter-pound deep-fried hot dogs. It’s one of a half-dozen or so restaurants he co-owned around Oklahoma City, including the original Pops, famous for its 66-foot-high sculpture of a soda bottle on the side of the famed Route 66, 30 minutes outside of town.

Duck-Fat Fries

Later that day, McClendon visited another restaurant venture in the same shopping center, the swanky Coach House. It has been a city fixture since it opened in 1985, during one of the toughest economic slumps in modern Oklahoma history. He often used the back room as an extension of his office, entertaining visiting bankers and businessmen with plates of duck-fat fries and his encyclopedic knowledge of wine. McClendon was there to meet with co-owner Kurt Fleischfresser to discuss renovation plans. He had just one question: Would they keep the back room as the work continued? Fleischfresser assured him they would.

“He had a super amount of energy,” Fleischfresser said. “He always made you want to do good because he was so excited to do it.”

Front-Row Seat

Good news, though, was scarce for McClendon everywhere he went, even an outing on Saturday night to watch a Thunder game, the basketball team he partially owned and helped bring to Oklahoma City from Seattle. Wearing a blue-shirt, sleeves rolled-up, he took his usual front-row seat on the baseline near the Thunder bench.

What looked to be a brief respite from his business woes turned into a heart-breaker. McClendon could only stand with his hands at his sides as Golden State Warriors’ star Steph Curry sank a last-second three-pointer to hand the Thunder an overtime loss. McClendon left the same way he always did, walking through the private back corridor of Chesapeake Arena.

By Tuesday morning -- one day before he died and just hours before the world learned of his indictment -- McClendon was still firing off e-mails on future projects.

White-Water Rapids

Among those he messaged was Mike Knopp, a lawyer-turned-rowing-coach who was as close to McClendon as just about anyone. The pair had been working on the final phase of a decade-long project to transform a waterless, grassy ditch steps from downtown into a $100 million Olympic rowing venue. The nonprofit Oklahoma City Boathouse Foundation, with McClendon as chairman and Knopp as executive director, was two weeks away from completing a white-water rapids course for the May 7 U.S. Olympic slalom trials.

In McClendon’s final e-mail exchange with Knopp, the subject was mundane: trying to find a date for their next foundation board meeting.

At around 5:30 p.m., a federal grand jury in downtown Oklahoma City handed up the indictment. McClendon quickly cried foul.

“I have been singled out as the only person in the oil and gas industry in over 110 years since the Sherman Act became law to have been accused of this crime in relation to joint bidding on leasehold,” McClendon said in a statement within hours of the indictment. “I will fight to prove my innocence and to clear my name.”

‘Good to See You’

Around 8:00 a.m. the next morning, a business associate received an e-mail from McClendon. The two had bumped into each other the evening before at an Oklahoma City restaurant where McClendon was dining with his daughter, Callie Katt. McClendon seemed normal, the person later told Marcus Rowland, who spent 18 years as Chesapeake’s chief financial officer under McClendon. The e-mail was little more than a "good to see you last night" and discussion of some business matters, Rowland said.

Not long after McClendon sent that message, he climbed into his SUV and drove off. As he cruised north along a two-lane country highway, he picked up speed, traveling well above the posted 50 miles per hour. With thick, bushy trees on both sides of the road , McClendon had limited maneuvering room. His car collided with a concrete wall supporting a highway overpass at 9:12, according to the initial police report.

Hit Head-On

The details of the crash still have police investigators scratching their heads: The front-end of his car hit the overpass support head-on. They have yet to determine whether it was an accident or a suicide but their early comments suggest the embattled shale tycoon may have intentionally crashed his car.

"He pretty much drove straight into the wall," police officer Paco Balderrama saidshortly after the crash. “There was plenty of opportunity for him to correct and get back on the roadway, and that didn’t occur."

As dusk set on the desolate site one day after the crash, Oklahoma’s famous red-toned dirt had turned an acrid, charred black. A makeshift memorial marked the site of impact: yellow and red roses placed carefully at the base of two crosses adorned with baseball caps and draped with pink and white polka dot ties -- one of McClendon’s favorite patterns. A single, white Chesapeake hard hat lay in the dirt.

No comments:

Post a Comment